The remembering is sharp – every detail, each decision, the cleaving of her life.

Alicia Gonzales remembers sitting on the bed in her dorm room at Marshall University. She remembers what she wore – sweatpants and a long-sleeved shirt, no make-up, hair fastened in a French braid. It was approaching afternoon. She didn’t want to be alone with him, but the friend who was with her left, so she was alone with him.

She remembers the way she tensed when he began to talk about his body count. He’d had sex with 16 people, he told her. She remembers all the excuses she made, initially plausible, increasingly desperate – the door’s unlocked, my roommate will be home soon, in my religion we don’t have sex on Mondays.

When she pointed out someone could walk in, he got up and deadbolted the door. That’s when she knew, when the voice inside her said, “You’re going to get raped.”

Her perpetrator, fellow Marshall student Joseph Chase Hardin, was more than 6 feet tall and 250 pounds, and he was aggressive and undeterred – by her “nos,” by her nails across his flesh, by every effort she made to get away.

Lawyers would later tell her she should have screamed louder, but it was difficult with his hands around her neck. Afterward, blood dripped down her leg, stained the comforter, trailed to the bathroom, colored the toilet.

“He just stood up like everything was fine,” she said. “He literally walked to my sink. He cleaned himself off. He had blood and everything all over him. He had scratches all over him. He cleans himself off, puts his clothes on, and he comes up to me.

“And the very last thing he ever said to me was, ’17.’”

When he left, Gonzales did what women are taught to do, the things that can feel impossible to do. She preserved the moment and preserved her body. She sent a group text to her two closest friends, told them something bad had happened and they needed to come right away.

Her friends arrived like detectives, bagging evidence, taking pictures. They told Gonzales it was time to go to the hospital. They helped her back into her original clothes and packed extra ones. They grabbed a male friend as an escort.

The nurses administered a rape kit, swabbing every inch of her, which felt like a re-violation. The police came, but Gonzales said she couldn’t speak. The next morning, on Feb. 2, 2016, Gonzales walked with her friends to the Marshall University Police Department and filed an official report. The police informed Lisa Martin, the school’s director of student conduct.

What came next, according to Gonzalez and the lawyers who would represent her in her civil suit against the university, was a litany of decisions that demonstrated Marshall’s carelessness toward Gonzalez – her rape, her trauma, her education. It is a case study into how, five decades after the passage of the landmark Title IX law banning sex discrimination in education, schools continue to fail women.

About the series

USA TODAY’s “Title IX: Falling short at 50” exposes how top U.S. colleges and universities still fail to live up to the landmark law that bans sexual discrimination in education. Title IX, which turned 50 this summer, requires equity across a broad range of areas in academics and athletics. Despite tremendous gains during the past five decades, many colleges and universities fall short, leaving women struggling for equal footing.

-

Despite men’s rights claims, colleges expel few sexual misconduct offenders while survivors suffer: Read the investigation

In the U.S., 1 in 5 college women report being sexually assaulted during their time at school, and the trauma of these violations ripples across their education. Some have trouble attending classes and see their grades drop, others take long leaves of absence to heal or avoid their perpetrators. Some transfer or quit school altogether.

Title IX was supposed to address that. In addition to mandating equity in academics and athletics, the federal government also requires schools crack down on sexual harassment and sexual violence.

Guidance from the U.S. Department of Education in 2011 crystallized that mandate: Schools must designate Title IX coordinators. They must immediately investigate allegations of rape, stalking and dating violence. They must offer accommodations to victims and levy sanctions on perpetrators. They must ensure that students feel safe on campus and can obtain an education free from gender-based harassment or violence.

With Hardin, Marshall followed the letter of the law but missed the spirit. By the time the school finally expelled Hardin for sexual misconduct, Gonzales had transferred to another university, and two additional students accused him of rape.

Accountability came too late.

‘The one person I had on my side literally gave up on me’

Things didn’t go south for Gonzales right away. Initially, school officials seemed to want to help her.

Court documents show Martin met with Gonzales in her office on February 8, 2016, and Gonzales said that’s when she told her in detail what had happened. Gonzales remembers the blinds were drawn, which felt fitting. Martin, who at the time was head of student conduct and also conducted Title IX investigations, was empathetic. Gonzales felt reassured and validated.

But, Gonzales said, as the Title IX process wore on, she felt as though the no-contact order wasn’t being enforced. Gonzales said Hardin had stood outside the learning research center where she worked, which she felt was taunting. A graduate assistant in the office of student conduct told Martin he had witnessed Hardin exiting a residence hall, where he was forbidden, according to court documents.

Gonzales said Hardin posted a picture of himself and some of their mutual friends on social media, wearing her headband at a basketball game, which she realized he had stolen from her room the day of the rape. Gonzales said she would report each incident to Martin, who would tell her “we’ll investigate,” but nothing would happen.

Five weeks after filing her initial report with campus police, Martin found Hardin had violated the school’s sexual misconduct policy and recommended he be expelled.

Hardin appealed and, per school policy, was allowed to remain on campus.

Hardin hired two private attorneys, and Gonzales said she was in a meeting with Martin and her mother in late April when she asked Martin if she needed a lawyer, too. She said Martin replied, “No, I’m going to represent her.” According to court documents, Martin says she informed Gonzalez of her right to an attorney.

Gonzales said Hardin’s lawyers seemed to shift the process in his favor. Gonzales said as she was leaving class one day, walking past the Memorial Fountain in the heart of Marshall’s campus, Martin called her, panicked, and asked her to delete all their correspondence. When Gonzales asked why, she said Martin told her Hardin’s attorneys were coming after her, and she feared losing her job.

“I would never forget that,” Gonzales said. “The one person I had on my side literally gave up on me.”

USA TODAY requested an interview with Martin, but she directed USA TODAY to Marshall’s communications department, which would not answer specific questions about Gonzales’ case.

Sociologist Jacqueline Cruz, who studies how university administrators experience creating and implementing Title IX policies, approaches her work with the belief that people in Title IX roles are well-meaning. All administrators she has interviewed said they cared deeply about their students and about equity, and many said they resented media characterizations that suggested they are apathetic to both.

What Cruz found was that administrators are fearful of being seen as biased and terrified of media attention or bad press. Some expressed pressure to maintain “institutional reputation,” and many told her there is intense pressure to be neutral. This means when an administrator hears an account of sexual violence, they feel as though they can’t fully empathize with a complainant. They feel a need to be empathetic toward the accused, too, even when the evidence against them was overwhelming.

Administrators Cruz interviewed told her “I’m a neutral party.” A more productive statement, she said, would be to state, “I’m here to stop sexual violence.”

“I don’t think you can be neutral about sexual violence. If we have laws that are there to end discrimination, then by definition, they’re not neutral,” she said.

In the spring of 2016, Gonzales was scared, traumatized and struggling in her classes. Hardin rescheduled his appeal hearing at least four times, which prolonged the process. Ultimately, it was scheduled for a Wednesday in May, the only day of the week Gonzales said she could not do. At 8:00 a.m. the next morning, she had an anatomy final.

During the hearing, the school permitted Hardin’s two attorneys to aggressively cross-examine her. Gonzales did not have a lawyer present. Gonzales remembers Hardin’s lawyers claiming her blood was not from sexual trauma, but from her period. They asked her how old she was when she first started menstruating. They asked her how many sexual partners she had had.

At one point, when his lawyers were discussing her assault, she could hear Hardin mutter under his breath, “You wish that happened.”

According to court documents, Hardin’s counsel claimed there was no physical evidence, which was untrue. Physical evidence, according to Gonzales’ lawyer Amy Crossan, included Gonzales’ rape kit, bedding, clothes, and a picture of her bloodied toilet. But this evidence was not used during the hearing, according to Marshall, due to the ongoing criminal case against Hardin, who had been charged with second-degree sexual assault.

The majority of sexual assaults are never reported to police, but Title IX legal experts say in cases where a police report is filed and physical evidence exists, it’s typical for police to withhold that evidence until the criminal process is complete. It’s also common for schools to delay their Title IX investigations until the police give them the green light.

Tensions between the Title IX process and the criminal process reflect both a desire for universities to offload sexual assault issues to law enforcement, as well as a misconception among universities that they must defer to the police, said Emily Martin, vice president for education and workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center.

“(There) is a deep cultural confusion right now, which I think is feeding this idea that the police go first, that’s the police’s job, really, and the school can’t do anything until the police have done their work,” she said. “The Title IX process can and should proceed concurrently with the criminal process.”

After her testimony, Gonzales, who was distraught, waited in another room. Eventually, she heard people filing out. Then, in a scene she likened to Bender’s iconic fist pump at the end of “The Breakfast Club,” she says she saw Hardin bounce down the hall and raise his fist triumphantly as his friends laughed and clapped.

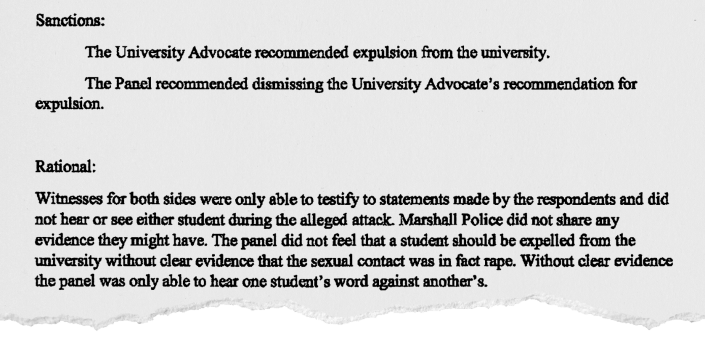

Hardin had won his appeal. His finding of responsibility, as well as his expulsion, were overturned.

Gonzalez said Lisa Martin was crying when she found her.

“I’m so sorry,” Gonzales recalled her saying.

Gonzales got a D on her final.

‘He’s just going to do it again’

The hearing wasn’t the end. The university and Hardin would continue to go back and forth on his fate, while Gonzales struggled to stay afloat.

Despite the decision reached at the hearing, court documents show that afterward Carla Lapelle, the interim dean of student affairs, recommended to then-Marshall President Jerome Gilbert that Hardin be suspended from campus until the outcome of his criminal case. Gilbert accepted that recommendation and Hardin was told he could attend classes online instead. But this was unsatisfactory to Gonzales. Since Hardin’s future at Marshall remained unclear, Gonzales and her family decided she could not safely continue her education at Marshall. Gonzales transferred, and that fall began her freshman year again, at a university in Pennsylvania.

On January 11, 2017 – nearly one year after the incident – Hardin took a plea deal that reduced his felony sexual assault charge to a misdemeanor battery charge. Hardin asked Marshall to be reinstated, and Title IX Coordinator Debra Hart granted Hardin’s request. She reasoned that because he was convicted of battery – instead of sexual misconduct – and needed to be on campus to finish his degree, he should return. She also determined that his presence would not upset Gonzales since she had transferred and was no longer on campus. Hart granted his request to return, with restrictions.

Gonzales was enraged. She saw the school putting the educational needs of Hardin above the safety of its own student body.

“I remember saying out loud, ‘he’s just going to do it again,'” she said.

Gonzales filed a civil lawsuit against the school one year later, alleging officials demonstrated “deliberate indifference” in deviating significantly from the standard of care outlined by Title IX.

She lost the case, which her lawyer Amy Crossan said reflects the high burden students face in holding universities accountable for Title IX violations.

U.S. District Court of West Virginia Judge Robert Chambers ruled that Gonzales did not establish that Marshall was deliberately indifferent to her harassment.

Among Marshall students, Gonzales’ story is notorious, held up as an example of the school’s mistreatment of survivors of sexual assault, not only because it refused to expel Hardin, but because in the absence of any meaningful discipline, less than two years later he raped again.

‘When it was over, he was like, “OK, well I got to get home.” Just like it was completely normal’

Ripley Haney met Hardin at the Baptist Campus Ministry the first semester of her freshman year in 2018.

Haney said Hardin had a girlfriend he was dating on and off. Hardin and Haney would text and flirt, but little else. One time, when he was “off” with his girlfriend, they went to a park with their Bibles and kissed.

Hardin told Haney he wanted to explain everything, told her Gonzales was crazy, that she had accused him of rape because he wouldn’t take her to the winter formal. Haney thought she was doing the right thing, giving him the benefit of the doubt.

Haney told Hardin she was a virgin and that it was important she remained one until marriage. On October 7, 2018, Haney and Hardin planned to meet in a park, but Hardin suggested they head to the Huntington Museum of Art, which is located on a secluded hill. Haney agreed, parking underneath a light post in the main lot, but Hardin suggested she park around back, so she moved her car.

They kissed, and she was comfortable with that. They had oral sex, and she was comfortable with that, too. But then he tried to have vaginal intercourse. She was not OK with that, and she told him. He ignored her, so she kept telling him, and physically stopped him. Then he raped her anally.

She estimates she told him no 50 times.

“When it was over, he was like, ‘OK, well I got to get home.’ Just like it was completely normal,” she said.

Haney got into the front seat to drive him back to his car. She wasn’t sure what else to do. The whole way home, she kept putting one hand on the gear shift and the other on the window to lift herself off the seat, because it was too painful to sit.

“I was so ashamed, and I didn’t want my parents to know that we had done anything, that I had lied to them about where I was, that I had done anything with him, let alone that he raped me. I was at home, and my little sister was in her room, and my parents are home, and they have no idea what just happened. I ended up saying, ‘Hey Harper,’ that’s my little sister, ‘Let’s go get ice cream.’ So we went and got ice cream.”

‘Everybody just gets the impression that she blows everything off’

Crossan, Gonzales’ lawyer in her civil suit, also represented Haney during her Title IX hearing. When she decided to represent Haney, she was curious whether the university could be held liable for her assault, but ultimately determined it could not. In the 4th Circuit, Crossan said, the law states that Marshall would have had to know that Hardin was going to rape victim two, not that he had already raped victim one.

Having evaluated Gonzales’ Title IX process and been present for Haney’s hearing, Crossan determined there were improvements, including Marshall’s hiring of a competent Title IX investigator, though she is no longer at Marshall. Haney’s Title IX report by investigator Shana L. O’Briant Thompson was detailed, thorough and demonstrated an understanding of sexual trauma.

But Crossan’s assessment of improvements to Title IX at Marshall is little comfort to Haney, who said her experience, particularly with Hart, the Title IX coordinator, left her traumatized. Crossan agrees Hart is a problem.

“She doesn’t have the confidence of the students and she doesn’t have the confidence of the faculty and staff,” Crossan said. “Everybody just gets the impression that she blows everything off, that she will never find anything negative against the university.”

Haney reported her rape six weeks after it occurred, a delay in reporting which is common for victims of sexual assault. She disclosed it to her Bible study leader and eventually to the police. When she met with a Huntington police officer in early November, she said she was told the department would contact Marshall on her behalf and that the university would issue a no-contact order. With this assurance, she decided not to pursue a restraining order.

But Hart didn’t put a no-contact order in place until February 21, three months after Haney filed her police report.

When USA TODAY questioned Marshall on the lag time between her police report and the no-contact order, the school cited a number of issues, including the assault occurring off campus, the school’s winter break, and the Huntington Police Department’s request that the Title IX process be suspended until it had gathered information on the criminal investigation.

Marshall’s approach reflects a widespread misperception among the public and among some school administrators that Title IX is a “quasi-criminal sexual assault law for schools,” said the NWLC’s Emily Martin. Instead, she said, it’s a civil rights law that instructs schools to ensure that when somebody experiences sexual assault or harassment that it does not put an end to their education.

“This particular example is especially troubling,” Martin said, “because even if there was some situation where the police had some worry that the evidence might be in some way compromised if the Title IX hearing went forward before the criminal procedure … when you’re talking about something like a no-contact order, that should be an interim measure that the school puts in place while its investigation is ongoing.”

On January 29 and January 30, 2019, the university’s associate general counsel and campus police, respectively, notified the Title IX office that the Huntington Police Department had concluded its criminal investigation and the Title IX process could proceed. It would be another three weeks before Hart would contact Haney and issue the no-contact order.

Haney said during the school’s Title IX investigation, she interacted with Hart several times. She characterized her as unsympathetic. She said she felt as though Hart “was always on Chase’s side.” In one meeting, which Haney recorded, Hart admonished her for calling Hardin a rapist, saying that “we don’t have any record of that.”

The month after Haney’s no-contact order was put in place, she learned a girl she was friendly with was spending time with Hardin. She texted her to be careful. The next day, Haney received an email from the university stating that “you may have violated the no contact order.”

“I’m freaking out and crying. I had to skip class to go to a meeting for Title IX. I got in there to the meeting, and I was sitting down. The first thing that I said was, “How did I violate the no-contact order?”

During the conversation that followed, which Haney recorded, Hart flip-flopped on whether Haney had violated the order. First she said she did not. Then later in the conversation, she said it’s safer not to text third parties about what happened because it could be considered a violation. Haney asked directly if she was allowed to. Hart said, “you can.” Then later Hart again said texting others about her Title IX case could violate the no-contact order.

The no-contact order stated that Haney “must not have physical contact with or proximity to, or direct verbal, electronic, written, and/or indirect third-party communications with” Hardin. Haney did not violate that mandate. The no-contact order also stated that the investigation was “confidential,” which NWLC’s Emily Martin said may have been what Hart was intimating when she suggested Haney may have violated the order, though Martin called the imposition of confidentiality “problematic.”

Haney said she was trying to protect the girl, because she felt the school would not.

“As a good person I’m going to text a friend and tell them if they’re with a rapist,” Haney told Hart.

“You accuse him of being a rapist. We don’t have any record of that. He pleaded guilty to a battery charge. Are you aware of that?” Hart said.

“Yes, but he is a rapist,” Haney replied.

In Haney’s case, Hardin was found guilty of violating the sexual misconduct policy, and on June 3, 2019, Haney received a letter stating the school was recommending Hardin be suspended.

Three days later, Hardin was indicted on two counts of second-degree sexual assault involving Haney, and two counts of second-degree sexual assault involving another Marshall student. The second student declined to be interviewed, and it is USA TODAY’s policy not to name victims of sexual assault without their consent.

On the same day of the indictment, Haney appealed Hardin’s sanction as too lenient.

Five days later, on June 11th, Hardin was finally, officially, expelled.

“I am not so sure that they would have expelled him but for the fact that … right around the time the decision was due, he was arrested and charged with the two other rapes,” Crossan said.

A year later, Hardin was found guilty of two counts of second-degree sexual assault for raping Haney; he was found not guilty of the two counts involving the third woman. A judge sentenced him to serve 20 to 50 years in prison. His projected release date is February 11, 2045, according to the West Virginia Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

‘It took more victims for there actually to be some type of justice’

It’s been more than six years since Gonzales’ assault and four since Haney’s. Marshall University has had more than half a decade to improve its Title IX process. Crossan said the school has made important changes, including hiring a lawyer to serve as its Title IX investigator, and conducting a more orderly and fair hearing process. But USA TODAY’s investigation found Marshall still holds few students accountable in Title IX cases, and victims remain critical of the way those cases are handled.

Data provided by Marshall from January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2020 shows Marshall receives few Title IX reports and investigates most of them but finds very few students responsible. Only 18% of formal investigations resulted in findings of responsibility – one of the lowest rates of schools examined by USA TODAY. This suggests a high burden for complainants to prove they were assaulted, stalked and harassed, and may also indicate that a large number of complainants are dropping out of the process.

Of the 10 students found responsible, eight avoided expulsion or suspension, instead being ordered to attend Title IX training and counseling.

Last fall, a Marshall University student posted a TikTok criticizing the university’s handling of her sexual assault report. The post was viewed more than 175,000 times and garnered nearly 30,000 likes. USA TODAY reached out to the person who posted it, but she declined to comment.

Comments on the TikTok called the process of Title IX at Marshall ineffective and re-traumatizing. Some warned prospective students to stay away from the university, citing a failure to protect victims of sexual assault.

One user remarked that “Marshall’s response to Title 9 is the reason so many are afraid to come forward.” Another claimed she had been “Laughed at by MU title IX people.” One wondered, “when will our campus take it seriously?”

Some of the responsibility falls on Marshall. Some of it reflects fundamental problems with the way Title IX is conceived of and applied, which hampers the law from solving the problem it was created to address. It’s tempting to blame these problems on a handful of bad actors, but given the omnipresence of Title IX failures at universities across the country, it’s clear problems are systemic.

In a 2020 article published in The Journal of Higher Education, sociologist Jacqueline Cruz wrote that, “Within the confines of neutrality, administrators must juggle the belief that they need to be empathetic to all students with the realities of the traumatic consequences of being sexually violated, and the knowledge that public scrutiny could cost them their job. This is a delicate balancing act that can pit what administrators know and feel against what they must do.”

In August of 2020, Gonzales traveled to West Virginia to attend Hardin’s trial. She was there to support Haney and the other woman in the trial. She was there for vindication.

“It’s sickening to say, but I had the ideal rape case,” she said. “I did everything they needed me to. All of the testimonies added up. He was the only one that was consistently lying. I went through everything that I did for him to get a slap on the wrist, and then it took more victims for there actually to be some type of justice.”

At one point during the hearing, she remembers Hardin laughed.

“He just thinks it’s a game, I guess,” she said.

Gonzales and Haney each said that after their cases went public, more than a dozen women messaged them privately to say, “he did this to me, too.”

When USA TODAY asked a spokesperson for Marshall if there was anything the school would like to publicly say to Joseph Chase Hardin’s victims, it declined.

Gonzales now lives in North Carolina and is a board-certified behavior analyst working with neurodivergent children, drawn to the field because she wanted to help people who felt voiceless. There isn’t a day that goes by that she doesn’t think about her rape, and the way in which Marshall made her feel her voice did not matter. She still wants the university to admit they wronged her, and to acknowledge they should have upheld Hardin’s expulsion.

Haney wants Hart fired, since she made the decision to allow Hardin back on campus after he raped Gonzales.

Haney remained at Marshall and is still pursuing a nursing degree. She got married this October to a partner she says makes her feel safe, respected and loved. But she is still coping with trauma. Haney is on medications for anxiety, depression and PTSD. She suffers from sleep paralysis. Last spring, during a night terror, her body buzzed and pulsed, and she dreamt she was yelling for help, yelling for her sister, while a figure pulled her off the bed.

When she opened her eyes, there was no one there.

Alia E. Dastagir is a senior news reporter at USA TODAY. To contact her, email adastagir@usatoday.com

If you are a survivor of sexual assault, RAINN offers support through the National Sexual Assault Hotline (800.656.HOPE and online.rainn.org).

Explore the series

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How a top university failed survivors during their Title IX cases